When we place the words “castle” and “London” in the same context, we generally think of the Tower of London as the only fortress in defence of the London area.

The cities evolution has seen its destruction and rebirth, forming the basis of the cities multi-phase defensives in a story that spans thousands of years.

1 Post-Boudican Roman Fort (CE 65-80)

The first post-Boudican fort was built at Fenchurch Street in response to the tribes of Britons revolting against Roman rule.

In CE 60 or 61, whilst the Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus was leading a campaign on the island of Anglesey off the northwest coast of Wales, the Iceni Queen Boudica, led a coalition of native tribes in a march across Britannia that led to the total destruction of Londinium.

In response, a fort was built in the Early Roman period (CE 65-80) around the site of 20 Fenchurch Street as a temporary structure. Excavations by the Museum of London at Plantation Place uncovered the north-east corner of the temporary fort and created a reconstruction plan based on these findings.

Possible fort-related features include clay-and-timber buildings, a large timber-lined water tank and a metalworking workshop.

2 Roman Fort (CE 120)

In succession to the temporary fort, a stone fort was built around CE 120, just north-west of the main population settlement.

It covered 12 acres and was almost square in size and 200m along each length. As Londinium grew, the fort was later absorbed into the defensive wall that surrounded the city and could house up to 1000 men with suitable barracks and gated entry.

A century later, the site was decommissioned as the military situation in the southern edge of Britannia had become more secure.

Today, the forts northern and western edges still remain visible, along with Saxon fortifications and medieval bastion towers as part of the Barbican and Museum of London complex.

3 Roman Wall

The London Wall is a defensive wall that encircled the City of London.

The wall was built between 190 and 225 CE, it continued to be developed by the Romans until at least the end of the 4th century, making it among the last major building projects undertaken by the Romans before Britannia looked to its own defences in CE 410.

Along with Hadrian’s Wall and the road network, the London Wall was one of the largest construction projects carried out in Roman Britain. Once built, the wall was 2 miles long and about 6m high, encircling the entire Roman city.

Despite Londinium being abandoned and left to ruin, the wall remained in active use as a fortification for more than another 1,000 years.

It was repaired when Anglo Saxon rule was returned to London by Afred the Great during a period of Viking sieges and raids, where he carried out building projects to rebuild crumbling defences, recut the defensive ditch (Roman fossa that encircled the walls of Londinium) and founded the re-settlement of Lundenburg within the walls.

The wall was further modified in the medieval period, with the addition of crenellations, gates and bastion towers. This formed part of a defensive line that incorporated The Tower of London, Baynard’s Castle and Montfichet’s Tower.

It was not until as late as the 18th and 19th centuries that the wall underwent substantial demolition, although even then large portions of it survived by being incorporated into other structures. Amid the devastation of the Blitz in WW2, some of the tallest ruins in the bomb-damaged city centre were actually remnants of the Roman wall.

4 Montfichet’s Tower

Montfichet’s Tower was a Norman fortress on Ludgate Hill in London, between where St Paul’s Cathedral and City Thameslink railway station now stand.

Little is known about the construction of Montfichet’s Tower. The first documentary evidence is a reference to the lord of Montfichet’s Tower in a charter of c1136 in relation to river rights.

The tower was probably built in the late 11th century, the name appears to derive from the Montfichet family from Stansted Mountfitchet in Essex, who occupied the tower in the 12th century.

A William Mountfichet lived during the reign (1100–1135) of Henry I and witnessed a charter for the sheriffs of London.

The last mention of the tower as a place of military significance comes in Jordan Fantosme’s chronicle of the revolt of 1173–1174 against Henry II.

The tower was eventually in ruin by 1278, according to a deed drawn up between the Bishop of London, where Montfichet’s Tower was included in the land sale with Baynard’s Castle to form the precinct of the great priory of Blackfriars.

Modern redevelopment gave the Department of Urban Archaeology of the Museum of London the opportunity to excavate the site between 1986 and 1990.

Archaeologists found ditches marking the outer defences, pits and a well that was interpreted as the bailey of the castle.

5 Baynard’s Castle

Baynard’s Castle refers to two buildings that existed on the same site between St Pauls Cathedral, where the old Roman walls and River Fleet met the River Thames, just east of what is now Blackfriars station.

The first was a Norman castle, constructed by Ralph Baynard (Sheriff of Essex) that incorporated an earlier Saxon fortification.

The castle was inherited by Ralph’s son Geoffrey and his grandson William Baynard, but the latter forfeited his lands early in the reign of Henry I (1100–1135) for supporting Henry’s brother Robert Curthose in his claim to the throne. John Stow gives 1111 as the date of forfeiture. Later in Henry’s reign, the lordship of Dunmow and honour or soke of Baynard’s Castle were granted to the king’s steward, Robert Fitz Richard.

The Norman castle stood for over a century before being demolished by King John in 1213. It appears to have been rebuilt after the barons’ revolt, but the site was sold in 1276 to form the precinct of the great priory of Blackfriars.

About a century later, a new fortified mansion was constructed on land that had been reclaimed from the Thames, southeast of the first castle.

The castle was rebuilt after 1428, and became the London headquarters of the House of York during the Wars of the Roses. Both King Edward IV and Queen Mary I of England were recorded being crowned at the castle.

By the end of the 15th century, the castle was reconstructed again as a royal palace by Henry VII, which Henry VIII gave Catherine of Aragon as a gift on the eve of their wedding.

Baynard’s Castle was left in ruins after the Great Fire of London in 1666, although fragments survived into the 19th century.

6 Ruislip Castle

Ruislip Castle is an 11th-century motte and bailey castle located in Ruislip in Greater London.

A timber castle would have stood on the raised motte (mound), beyond would have been a bailey (fortified enclosure) containing a cluster of huts that was introduced by the Normans as a means to subdue and administrate local populations.

Both would have been surrounded by a palisade and moat, part of the moat still survives today.

The castle was probably occupied for a very short period as there’s no record of Ruislip Castle in the Domesday book, however, groundwork on the site has been dated to the 9th century.

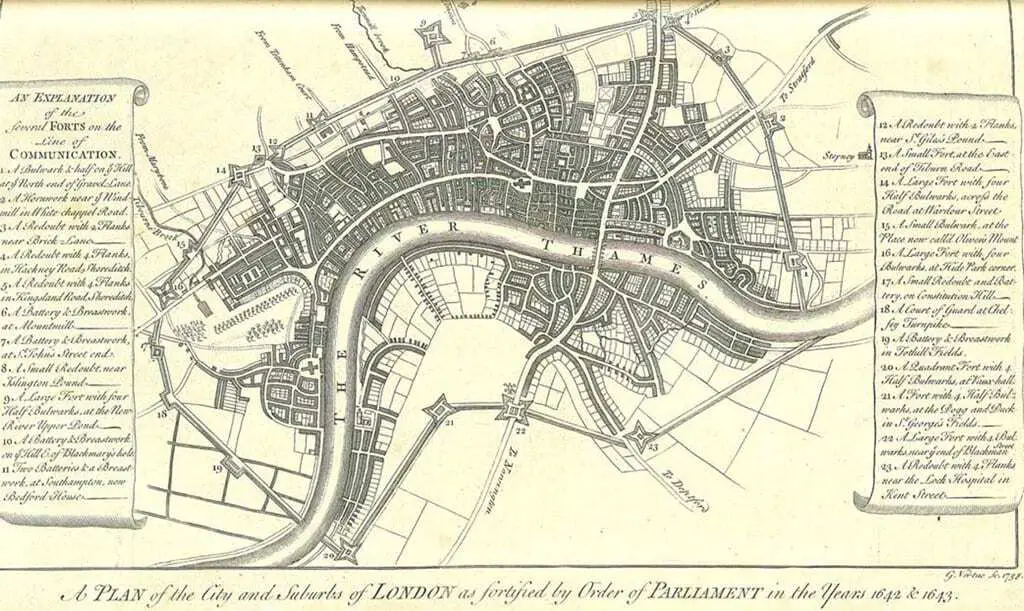

7 Lines of Communication

The Lines of Communication were English Civil War fortifications commissioned by Parliament in 1643 for intrenching and fortifying the City of London from attack by the Royalist armies of Charles I.

Much of the work was done by volunteer labour, organised by the trained bands and the livery companies. Up to 20,000 people are thought to be involved, and the works were completed in under two months.

These works principally consisted of a strong earthen rampart reinforced with a series of 23 fortifications of various types surrounding the whole City, and its liberties (including Southwark), at a distance of one and a half to two miles from the city centre.

7 London Stop Lines/Outer London Defence Ring

The Outer London Defence Ring was a defensive ring built around London during the early part of the Second World War. It was intended as a defence against a German invasion, and was part of a national network of similar “Stop Lines”.

In June 1940 under the direction of General Edmund Ironside, concentric rings of anti-tank defences and pillboxes were constructed in and around London. They comprised: The London Inner Keep, London Stop Line Inner (Line C), London Stop Line Central (Line B) and London Stop Line Outer (Line A).

The ring used a mixture of natural rivers and artificial ditches up to 20 feet (6 m) wide and 12 feet (4 m) deep, encircling London completely.