A study publishing in the journal Science Advances, has conducted a genetic study on the Xiongnu, the world’s first nomadic empire.

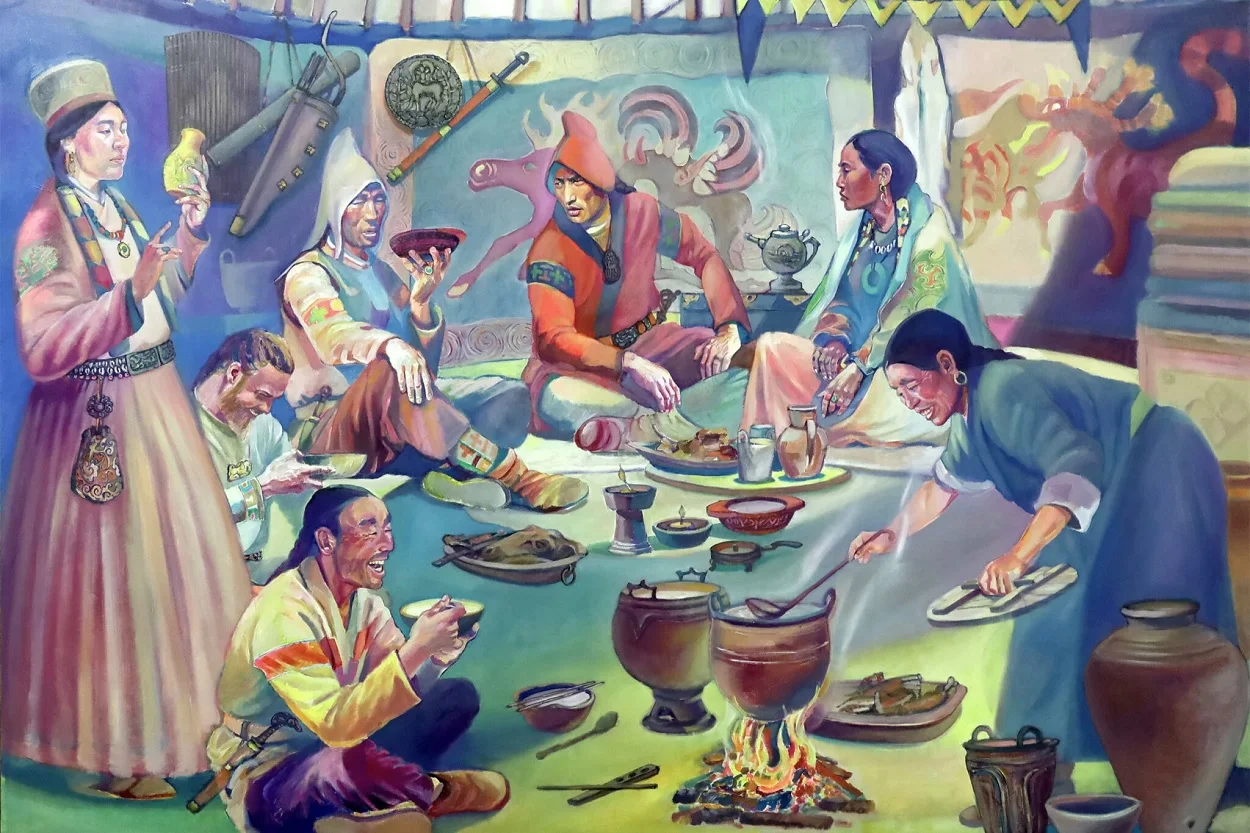

The Xiongnu were a tribal confederation of nomadic people that inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD.

Most of what we know about the Xiongnu comes from texts by the adjacent Chinese dynasties, which saw both cultures alternating between various periods of peace, war, and subjugation along the border.

According to Chinese accounts, the Xiongnu travelled on horseback, demonstrating remarkable combat tactics, and had powerful women in their societal structure. However, due to their lack of a structured writing system, historians possess limited knowledge about the intricacies of their culture.

Christina Warinner, associate professor of anthropology, said: “Physical evidence of these claims has been hard to come by. In most places in the world, the archaeological record abounds in residential domestic debris. The problem with mobile societies is they don’t stay anywhere long enough to build up that kind of archaeological record.”

What the Xiongnu did leave behind in the archaeological record are large mortuary complexes built from stone. A study published in 2020 reconstructed the genetic history of Mongolia over a span of 6,000 years that sequenced the DNA of human remains recovered from archaeological sites across the windswept country.

“At the time, we only analysed one or two individuals per site,” said Warinner. “From that, we could tell the Xiongnu were genetically diverse and multi-ethnic. But we weren’t able to say anything about their gender or social roles or about whether there was a relationship between their genetics and social status.”

To understand the internal dynamics of Xiongnu communities, scientists harvested genome-wide data for 19 individuals, with 17 yielding sufficient human DNA for analysis.

“We found that the aristocratic elite tombs were occupied by women,” said Warinner, who went on to list some of the symbolic goods buried with them — a gilded iron belt buckle, horse tack, a wagon, an ornamental sun and moon. “I think what we’re seeing is that as armies of Xiongnu warriors were going out and expanding the empire, elite women were governing the borders,” she said.

According to Warinner, the aristocratic women exhibited the least genetic variation as a collective, indicating that power was centralized within certain lineages. On the other hand, the male servants buried alongside them belonged to a vastly diverse group originating from far-flung areas of the empire and beyond.

Burial sites of lower-ranking elites exhibited a contrasting trend. In those cases, it seemed that arranged marriages were utilized to solidify relationships with recently annexed factions. When viewed collectively, the genetic lineage and familial ties in border settlements illustrate the varied techniques employed by the Xiongnu to expand their diverse empire.

“Some have proposed that the Xiongnu Empire was made up of a multitude of clans who themselves were fairly homogenous,” Warinner said. “We found that’s not true. They’re genetically diverse even within a single community.”

The DNA analysis, in addition to the archaeological findings, yielded poignant insights. Graves of adolescent boys contained miniature bows and arrows, perhaps as toys. In another burial, a woman and her new born appeared to have died during childbirth. An Egyptian faience bead depicting Bes, the deity who safeguards children, was discovered around the mother’s neck.

Header Image Credit : Christina Warinner