In a small rural village in West Kent England, remains a relatively unknown jewel of Tudor design and architecture – Otford Palace

In its heyday, Otford Palace was one of the main centres of both Royal and Ecclesiastical power in England. The palace was witness to many of the key events of the turbulent Tudor period and is a physical expression of the rivalry between two major players in the court of Henry VIII – The Archbishop of Canterbury, former Lord Chancellor of England, William Warham and Archbishop Wolsey, Henry’s right-hand man and Lord Chancellor of England.

The site of Otford palace lies in the parish of Otford, Kent, a few miles south-east of Greater London and adjacent to the Pilgrims Way, which tradition maintains was the road taken by pilgrims to the shrine of Thomas Becket at Canterbury.

The palace covers an area of just over one hectare and now occupies a combination of council-owned and private lands. Whilst the building today is a ruin, substantial parts survive that includes half of the north gallery that surrounded the main courtyard, the northwest tower to a height of over 11.5 metres, part of an adjacent gallery standing 3 metres high and large masonry remains in the front and back gardens of adjacent private dwellings.

The origins of the present site can be found in the Saxon period, but the first mention was for an earlier construction by Lanfranc Archbishop of Canterbury, which was valued at £60 in the Doomsday survey in 1086.

Over the next 400 years, the original manor house grew in size when Archbishop William Courtenay remodeled the house and created a stunning edifice with a new great hall in the late 14th century.

150 years later, Courtenay’s successor William Warham was to create a building that would have a profound effect on Tudor building design and its influence can be seen today in Hampton Court and many styles of Tudor architecture.

In 1514 Warham decided to completely redesign Otford, making it a building fit for a prince of the church and was to convey a clear expression of power and status. He demolished most of the existing buildings and constructed a new lavish palace that sets the current layout of Otford Palace.

No building plans or accounts of the construction survived, but a letter to Erasmus from Warham shows that only the chapel and one wall of the great hall remained in situ. The cost of this development must have been enormous for the time and contemporary sources believed the total cost for reconstruction to be over £33,000. The new palace, which incorporated ideas and designs imported from renaissance Europe, became an important location for the entertainment of both church and state.

It is worth noting that Lullingstone Castle built nearby in 1497 has features that resemble Otford Palace. It can be suggested that Warham was influenced by elements of its design and used the same local craftsman and building materials for his palace (this raises the question as to whether Lullingston was actually the precursor to the development of Tudor building design for Otford and Hampton Court).

In 1519, Henry VIII stayed at Otford Palace with his court and hunted in the great Deer Park that was attached to the palace grounds. Otford must have met with his approval as the following year Henry and Catherine of Aragon, along with the royal court stayed there again on their way to France for the meeting between Henry and Francis, King of France, at the Field of Gold.

Between 1532 and 1533 Princess Mary, the future Queen of England stayed there as a refuge from the political and religious turmoil that was engulfing England after the end of her mother’s marriage to Henry.

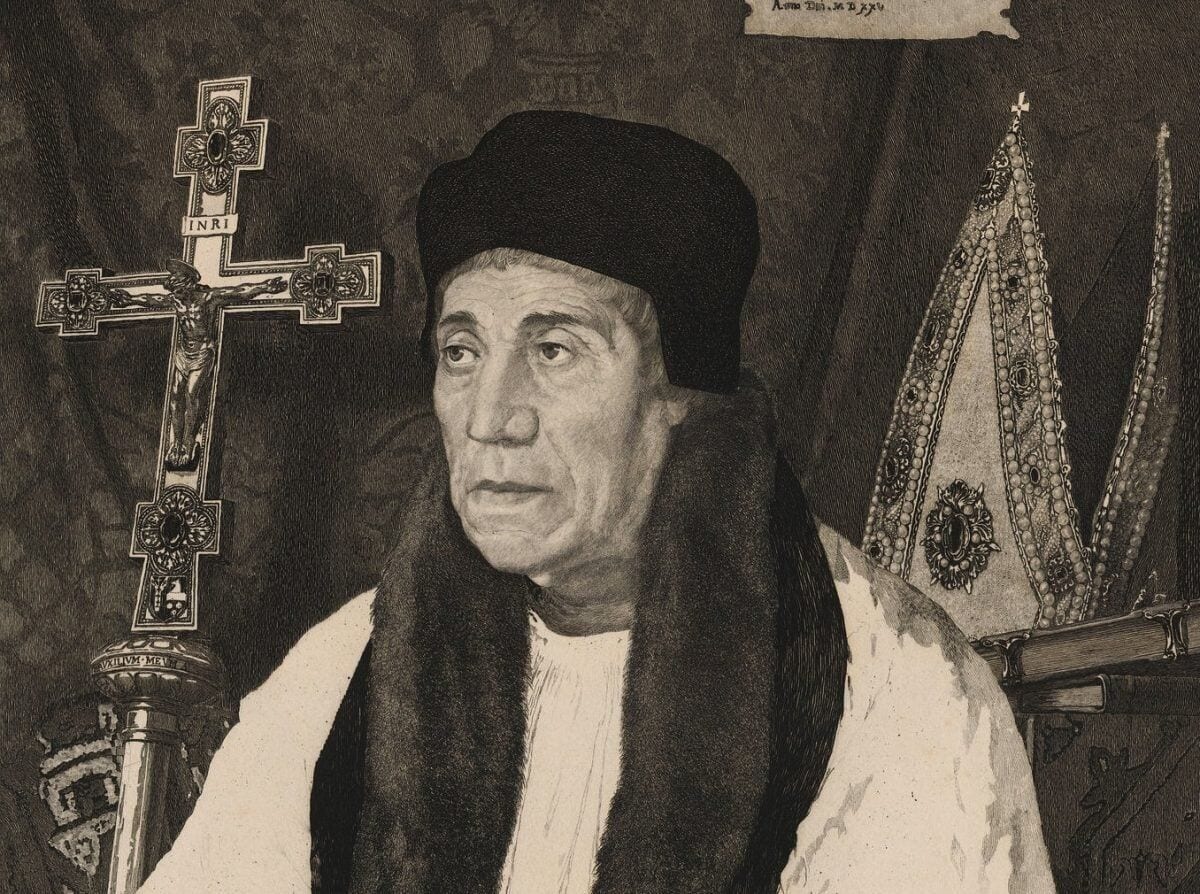

William Warham

William Warham seems to be a name that history has deemed to have forgotten and consigned to the scrapheap. Warham started his political career as a diplomat for Henry VII and became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1503 and Lord Chancellor in 1504.

A key achievement of Warham was in arranging the marriage between Henry VII’s son, Arthur, Prince of Wales, and Catherine of Aragon. In 1509 the Archbishop married and then crowned Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon King and Queen of England. In 1514 he consecrated his great rival Wolsey, the Bishop of Lincoln. He found the political pressure associated with the highest post in England too much and resigned the following year in 1515 but continued as Archbishop.

Cardinal Wolsey now took Warham’s place as the key political leader in Tudor England and intensified a rivalry that was to continue until Wolsey’s death. Warham didn’t totally retreat from the political scene and went with Henry to the Field of Gold in 1520 as mentioned earlier.

When we look at the plan and design features of Otford and compare them to Wolsey’s edifice at Hampton Court we can see a glimpse of the rivalry and dare I say it dislike that existed between both men. Both buildings share a number of common features, both sites were built over existing manor houses and they shared common architectural features.

Long galleries and accommodation buildings flanked both the main courtyards of Otford and Hampton Court. Hampton Court’s famous main gatehouse was on the west side and gave access to the main courtyard, which was rectangular in shape, and was nearly identical to Otford, however, Otford was bigger in size and grandeur and set the standard for Hampton Court.

Otford Palace was designed and laid out on such a scale that it even compares favorably with any of the largest contemporary palaces in England. At over 163m by 98m it covered an area greater than the later renaissance influenced Nonsuch Palace or the moated area of Eltham Palace.

A more personal insight into the role both buildings played in the power game between both men can be seen in a letter written by Warham to Wolsey in the winter of 1522. Warham tells Wolsey he is unable to travel to see him on the grounds of ill health. Warham also thanked him for the advice that he should live on high, dry ground rather than at Otford (which was damp and wet) and additionally for his offer of accommodation at Hampton Court. Historians suspect that Wolsey was being deliberately provocative and was clearly inferring that his building was far superior to Warhams Otford.

This rivalry did not have many years to run. Wolsey died in 1530 on his way to answer charges of high treason for his failure to resolve the problem of Henry’s marriage. Two years later, Warham died in his bed of old age; probably with a degree of satisfaction over Wolsey’s fall from grace.

Written by Diarmaid Walshe