Teōtīhuacān, named by the Nahuatl-speaking Aztecs, and loosely translated as “birthplace of the gods” is an ancient Mesoamerican city located in the Teotihuacan Valley of the Free and Sovereign State of Mexico, in present-day Mexico.

The earliest evidence of occupation dates from as early as 600 BC, with archaeologists discovering the remains of small, scattered villages in situ of where the city would later be founded.

The development of Teōtīhuacān can be identified by four distinct consecutive phases, known as Teōtīhuacān I, II, III, and IV, with phase I starting around 200 – 100 BC during the Late Formative era, when the inhabitants coalesced around sacred springs in the basin of the Teōtīhuacān Valley.

Some scholars suggest that the founders were the Totonac people, creating a multi-ethnic state since the city represents cultural elements connected to the Zapotec, Mixtec, and Maya peoples, although many studies dispute the Toltec origin as the Toltec culture peaked far later than Teotihuacan’s zenith.

During phase II from AD 100 to 350, the city population rapidly grew into a large metropolis, partly due to the economic pull and opportunities a thriving urban settlement presented, but also based on environmental factors suggested by the eruption of the Xitle volcano, forcing the migration from other settlements out of the central valley.

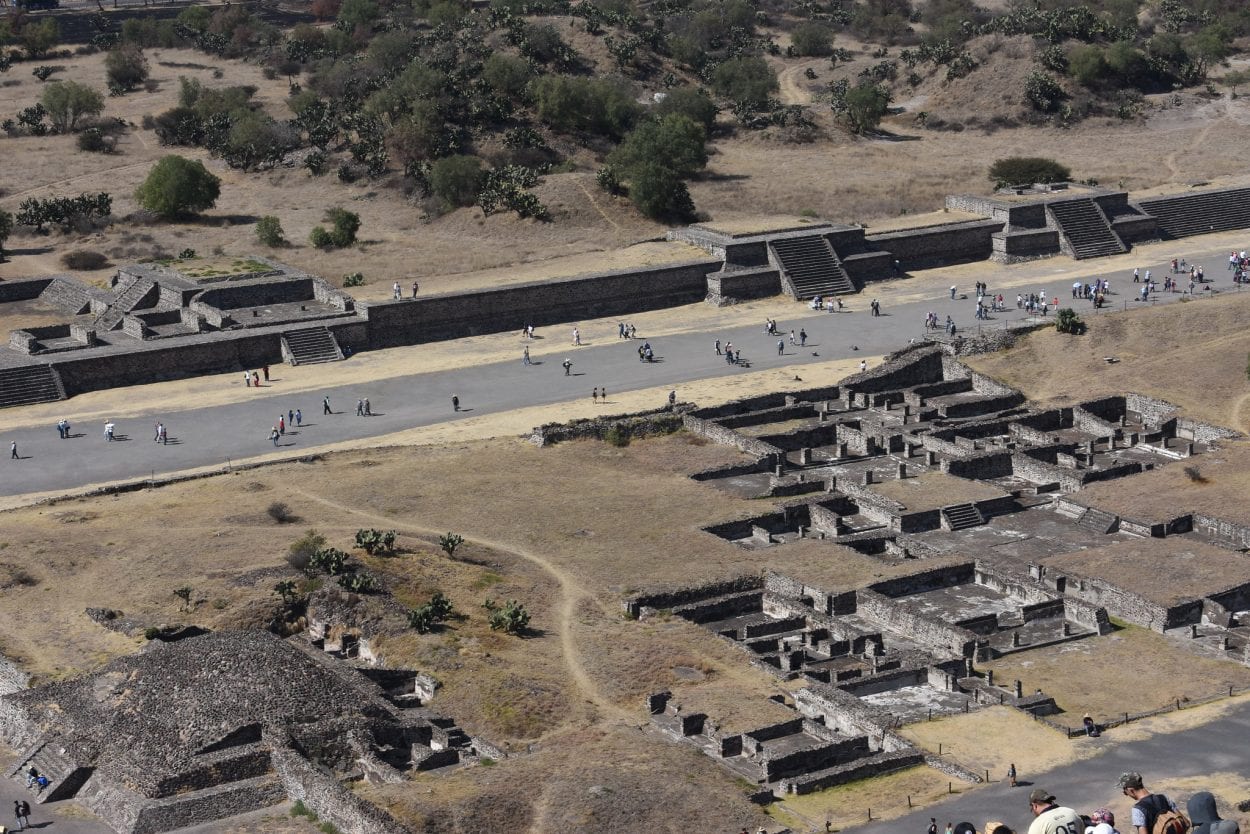

It was during this phase that many of the most notable monuments within Teōtīhuacān were constructed, including the Pyramid of the Sun (the third largest ancient pyramid after the Great Pyramid of Cholula and the Great Pyramid of Giza), the Pyramid of the Moon, the Avenue of the Dead, and the Ciudadela with the Temple of the Feathered Serpent Quetzalcoatl.

The urban layout of the city exhibits two slightly different orientations, which resulted from both astronomical and topographic criteria. The central part of the city, including the Avenue of the Dead, conforms to the orientation of the Sun Pyramid, while the southern part reproduces the orientation of the Ciudadela. The two constructions recorded sunrises and sunsets on particular dates, allowing the use of an observational calendar.

Phase III (also called the classical period) lasted from AD 350 to 650 and saw Teōtīhuacān reach its apex as a primate city. The city had an estimated population of 125,000 inhabitants (some estimates also suggest 250,000), and over 2,000 buildings covering an area of 4447.9 acres.

During Period IV between AD 650 and 750, the city went into decline with rapid population shrinkage. Scholars initially proposed that Teōtīhuacān was sacked and burned, but a closer study by archaeologists has determined that the burning was mainly confined to the elite housing compounds clustered around the Avenue of the Dead.

This has led to the suggestion that the city experienced civil strife, internal uprising, and power struggles between the ruling and intermediary elites that led to the eventual abandonment.

Studies of the contemporary climate record has also shown that during AD 535–536, the region suffered a series of droughts (possibly due to the eruption of the Ilopango volcano in El Salvador), causing the crops to fail and malnutrition in many of the juvenile skeletons excavated.

The sudden destruction of Teōtīhuacān was common for Mesoamerican city-states of the Classic and Epi-Classic period. Many Maya states suffered similar fates in the coming centuries, a series of events often referred to as the Classic Maya collapse.

Map of Teōtīhuacān – You can select full-screen mode on desktop by clicking on the “X” symbol beneath the map. For full screen on tablet or mobile. Click Here

Header Image Credit : pmonaghan – CC BY-SA 3.0